Weekly Grocery List for Athletes

Feeling overwhelmed at the grocery store is completely normal, especially when you’re managing training, school, work, and recovery. This Weekly Grocery List for Athletes takes the guesswork out of shopping so you can get in and out with purpose. Fill your kitchen with foods that boost energy, enhance performance, support recovery, and keep you healthy throughout the season.

How Alcohol Affects Training, Recovery, and Performance: What the Research Shows

This blog is about providing athletes with research-backed information so they can make informed, self-aware decisions about how much they drink and alcohol’s impact on overall health and performance. This isn’t a judgment about alcohol consumption or abstinence. Rather, it is a means of educating athletes so that they know how alcohol impacts their body and performance.

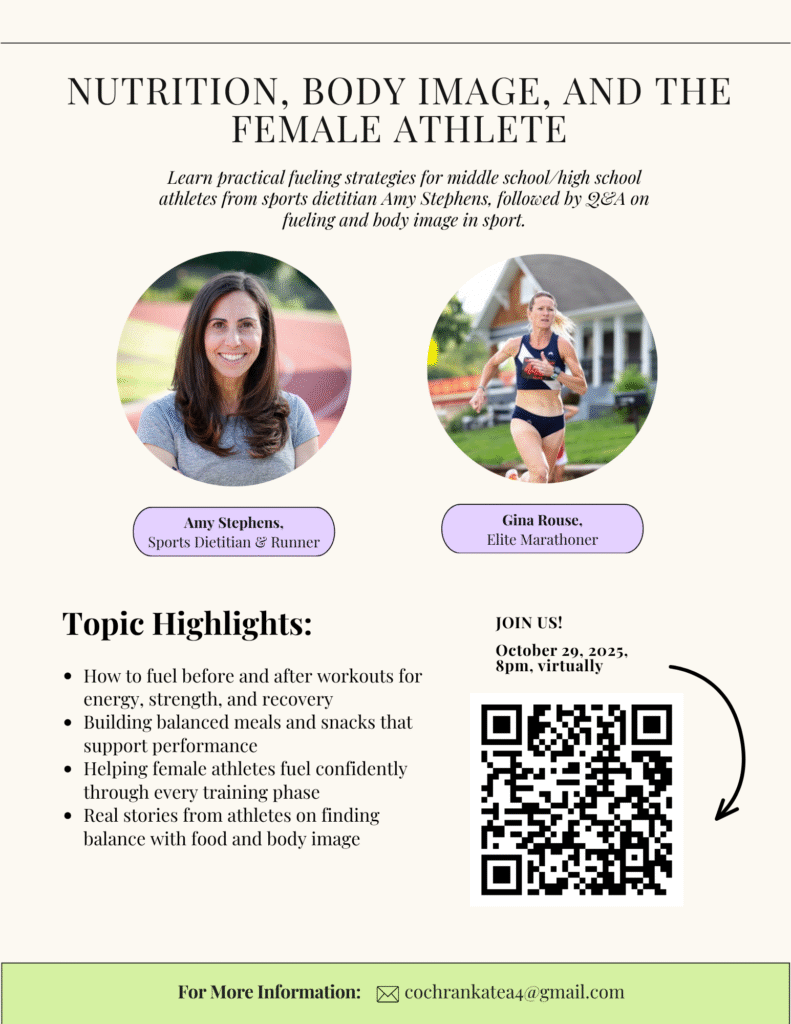

UPCOMING EVENT: FUELING THE FEMALE ATHLETE WITH GINA ROUSE 10/29 AT 8PM

Join sports dietitian Amy Stephens and elite marathoner Gina Rouse as we discuss fueling female athletes. Topics will include: how to fuel before, and after workouts for energy, strength and recovery, building balanced meals and snacks that support performance, and helping female athletes fuel confidently through every training phase.

Caffeine to improve athletic performance

Studies have shown an improvement in sports performance when caffeine is consumed before exercise (Clarke, 2018). Here are details about how caffeine works and the safe and effective dose that yields the best results.

PAST EVENT: MARATHON PANEL 10/8 AT 2PM

Hitting the wall is not inevitable. With the right fueling and pacing plan, energy levels can remain steady for the duration of your competition, and even provide a kick at the end.

Guide to Carb Loading for a Marathon

Plan, Prepare, and Prioritize Your Nutrition

Especially during taper week, it’s crucial to stay organized and mindful of your diet, particularly if you’re balancing a busy schedule. Even though we’re running less in the taper, nutrition is just as important as our bodies absorb all the training we’ve put in during our training cycle.

How to avoid hitting the wall during a marathon

Hitting the wall is not inevitable. With the right fueling and pacing plan, energy levels can remain steady for the duration of your competition, and even provide a kick at the end.

MACRONUTRIENT TRACKING: HELPFUL OR HARMFUL

By Kate, Cochran, NCAA Division III track and field athlete.

I often get asked my opinion on “tracking macros” and whether or not I do it as an athlete. While I think tracking your macronutrients as an athlete can be a good tool to ensure you’re eating enough to improve performance, I personally do not do it.

Sample presentation for high school athletes

These slides are examples from a presentation designed for high school athletes, highlighting key topics such as a performance plate, nutrient timing and hydration. They provide a preview of the type of content that can be shared in a team or classroom setting, offering practical, age-appropriate guidance that athletes can easily apply to their training, competition, and daily routines.

Fuel up: Power-Packed Meal Ideas for Athletes

My favorite meals for athletes! Refuel your energy with this list below.