Gut Training Essentials for Athletes

By Amy Stephens and Kate Cochran, Nutrition Intern

Many endurance athletes avoid fueling during long runs or rides because it feels uncomfortable or causes gastrointestinal (GI) issues. But often, that discomfort isn’t due to fueling itself—it’s because the gut hasn’t been properly trained. Being able to ingest carbohydrates during an endurance event will improve performance. It will enable you to exercise at a higher intensity for longer without running out of energy.

How to Fuel Your Best Workout

By Sonia Parashac, Intern

In this post, Sonia shares how she balances a busy college schedule while staying committed to daily movement—whether it’s a long run, a quick strength session, or a walk. She highlights the importance of fueling properly before, during, and after exercise to support energy, performance, and recovery.

When Should You Use Electrolytes?

Athletes often lose a significant amount of sweat when working out, especially in the summer months. Because sweat contains electrolytes, it’s essential to replace them to maintain proper hydration and muscle function. This ensures you perform at your best and recover eectively.

Best Supplements for Runners

The use of supplements within the world of sports and fitness is relatively widespread, being a means of addressing the various metabolic and dietary requirements of individual athletes.

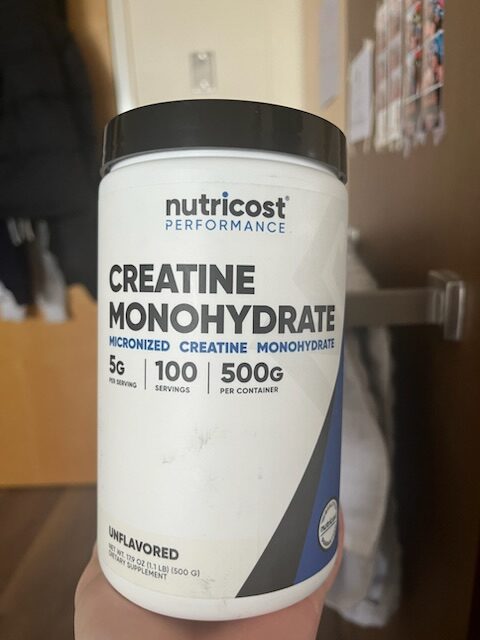

Creatine Supplement: Key Factors to Consider Before Use

Many amateur and professional athletes use creatine supplements to enhance their workouts and speed up recovery. Creatine is a naturally occurring compound found in the body and certain foods that provides a quick burst of energy and increases strength.

Nutrition for a Half Marathon: Fueling for Performance

Whether it’s your first half marathon or your 10th: Whether you’re aiming for a PR or running for fun, proper nutrition is key to sustaining energy, optimizing performance, and ensuring good recovery. This guide covers everything you need to know about fueling before, during, and after your race, along with common mistakes to avoid.

QUICK AND HEALTHY LUNCH IDEAS FOR COLLEGE STUDENTS

Eating a balanced lunch offers numerous physical, mental, and emotional benefits, making it especially crucial for college athletes. However, research shows that up to 60% of college students skip lunch due to their busy schedules and budget (Pendergast, 2016). Skipping this meal can negatively impact energy, hunger management, and overall well-being.

TOP FUELING OPTIONS FOR ENDURANCE ATHELTES

Here’s a list of the best fueling options for endurance athletes—designed to support energy, facilitate recovery, and keep performance strong. These snacks are easy to digest and perfect for on-the-go fueling. Keep them handy to stay energized throughout your day and training.

EATING DISORDER OR RED-S? THE KEY DIFFERENCES

TW: This content mentions eating disorders and body image.

Eating disorders are mental health conditions, whereas RED-S (Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport) is a physiological state caused by an energy imbalance. However, these conditions can overlap.

Winter Supplements for Runners

Winter months bring unique nutritional needs for runners, including reduced sunlight exposure, which increases the need for Vitamin D. Meeting nutrition goals through food is ideal, but supplements can be helpful when dietary intake is insufficient. Below are recommended winter supplements and their top food sources.